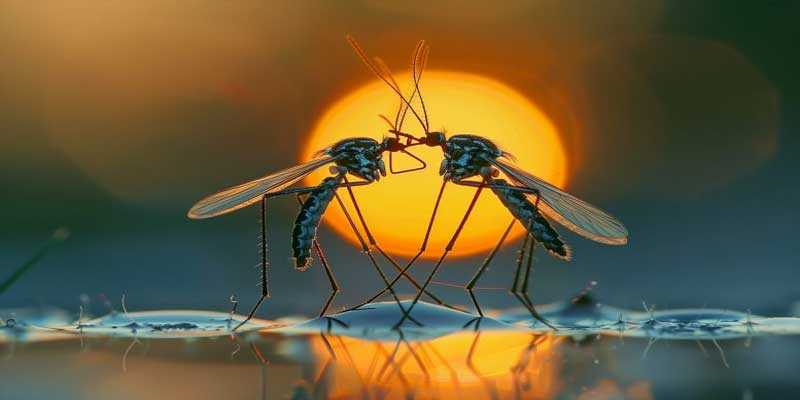

Mosquitoes buzz in sync to find love – a groundbreaking discovery from KFRI published in Nature’s journal

KFRI scientist Dr. Rajan Pilakandy has made a fascinating breakthrough in understanding the mating behaviour of mosquitoes, uncovering a natural phenomenon hidden in their characteristic buzzing.

A researcher at the Kerala Forest Research Institute (KFRI) in Peechi and a former scientist with the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Dr. Rajan's findings were recently published in Scientific Reports, a journal under the prestigious Nature group. His study reveals that the familiar mosquito swarm is not a chaotic cloud of insects, but rather a carefully orchestrated event in which mosquitoes seek partners by matching their wingbeat frequencies.

Male mosquitoes produce a wingbeat sound of around 600 Hz and search for females emitting frequencies around 500 Hz. When a male finds a female whose wingbeat closely matches his, they pair off from the swarm to mate. Following mating, the male typically dies within four to five days.

The female mosquito, on the other hand, begins a crucial phase of her reproductive cycle. She seeks a blood meal, not for sustenance, but to develop her eggs. Once she has fed, she lays her eggs, which hatch into larvae within three days. The larvae then transform into pupae within two weeks, and within another two days, they emerge as adult mosquitoes. Remarkably, the female mosquito can lay a second batch of eggs without mating again, as she stores the sperm from the initial mating in her body. For the second batch, she needs another blood meal; if one isn't available, she survives by feeding on plant juices for the remainder of her lifespan. Interestingly, unmated female mosquitoes do not bite humans or animals, highlighting that mating is a trigger for their blood-feeding behaviour.

During his research tenure with DRDO, Dr. Rajan raised mosquitoes in controlled cages for six months, using rabbits as the blood source for the females. He observed and recorded the distinct sound frequencies of mosquitoes, noting that each of India's 404 mosquito species has a unique wingbeat signature. This discovery suggests a complex and highly species-specific communication system among mosquitoes. His findings also emphasise the contrast between male and female mosquitoes—not just in lifespan, which averages a week for males and a month for females—but in behaviour and diet. Males, which do not bite, feed solely on plant juices throughout their short lives.

Dr. Rajan's work sheds light on an often-overlooked aspect of mosquito biology, offering potential avenues for future mosquito control strategies. By understanding how mosquitoes use sound to find mates, researchers might one day develop acoustic methods to disrupt their reproduction without resorting to chemical repellents or pesticides. This discovery adds a rich layer of knowledge to entomology, demonstrating how even the tiniest sounds in nature can have profound implications for life cycles and ecological balance.

Diganta Goswami, Vanlal Hmuaka, Sibnarayan Datta, Bipul Rabha, and Dev Vrat Kamboj were the co-researchers.

Published on: Saturday, July 5, 2025